The earthquake in Turkey is one of the deadliest this century. Here’s why

Nearly 8,000 people have been reported killed and tens of thousands of others injured by the devastating earthquake that rocked Turkey and Syria on Monday.

Thousands of buildings collapsed in the two nations and aid agencies are warning of “catastrophic” repercussions in northwest Syria, where millions of vulnerable and displaced people were already relying on humanitarian support.

Massive rescue efforts are underway with the global community offering assistance in search and recovery operations. Meanwhile agencies have warned that fatalities from the disaster could climb significantly higher.

Here’s what we know about the quake and why it was so deadly.

Where did the earthquake hit?

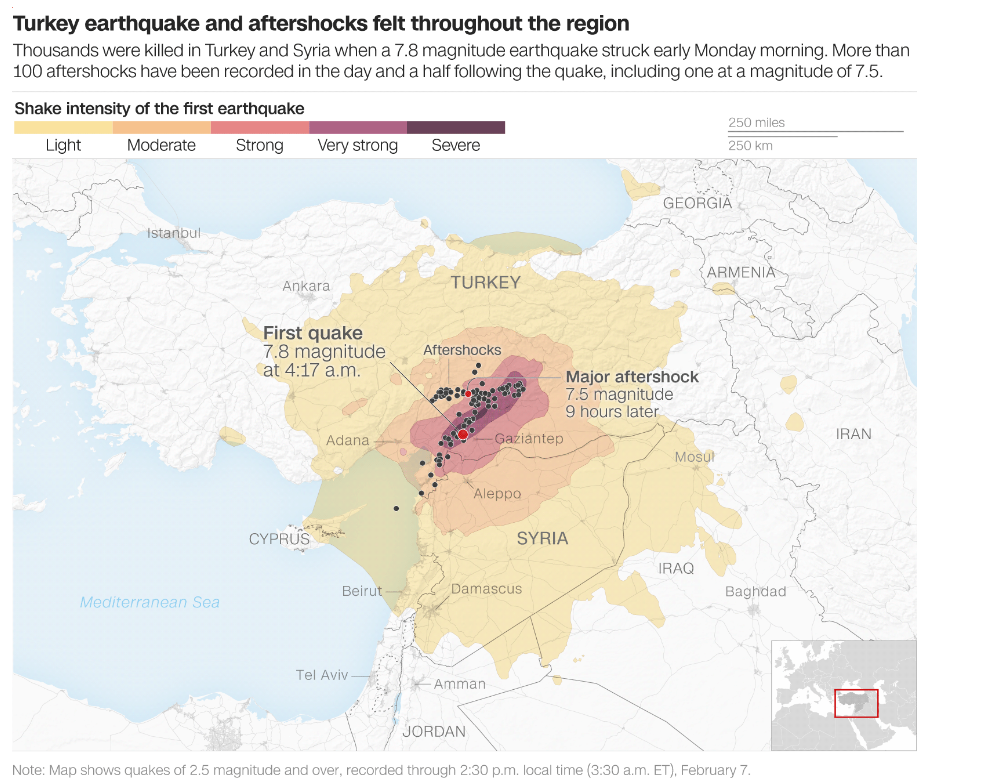

One of the most powerful earthquakes to hit the region in a century rocked residents from their slumber in the early hours of Monday morning around 4 a.m. The quake struck 23 kilometers (14.2 miles) east of Nurdagi, in Turkey’s Gaziantep province, at a depth of 24.1 kilometers (14.9 miles), the United States Geological Survey (USGS) said.

A series of aftershocks reverberated through the region in the immediate hours after the initial incident. A magnitude 6.7 aftershock followed 11 minutes after the first quake hit, but the largest temblor, which measured 7.5 in magnitude, struck about nine hours later at 1:24 p.m., according to the USGS.

That 7.5 magnitude aftershock, which struck around 95 kilometers (59 miles) north of the initial quake, is the strongest of more than 100 aftershocks that have been recorded so far.

Rescuers are now racing against time and the elements to pull survivors out from under debris on both sides of the border. More than 5,700 buildings in Turkey have collapsed, according to the country’s disaster agency.

Monday’s quake was also one of the strongest that Turkey has experienced in the last century – a 7.8 magnitude quake hit the east of the country in 1939, which resulted in more than 30,000 deaths, according to the USGS.

Why do earthquakes happen?

Earthquakes occur on every continent in the world – from the highest peaks in the Himalayan Mountains to the lowest valleys, like the Dead Sea, to the bitterly cold regions of Antarctica. However, the distribution of these quakes is not random.

The USGS describes an earthquake as “the ground shaking caused by a sudden slip on a fault. Stresses in the earth’s outer layer push the sides of the fault together. Stress builds up and the rocks slip suddenly, releasing energy in waves that travel through the earth’s crust and cause the shaking that we feel during an earthquake.”

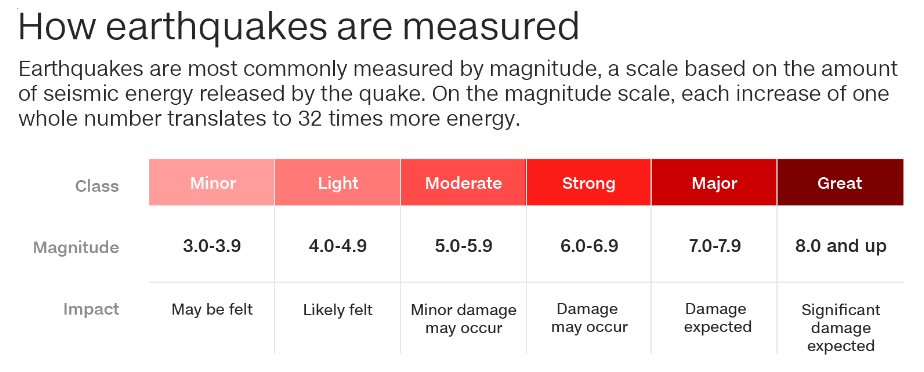

Earthquakes are measured using seismographs, which monitor the seismic waves that travel through the Earth after a quake.

Many may recognize the term “Richter Scale” which scientists previously used for many years, but these days they generally follow the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale (MMI), which is a more accurate measure of a quake’s size, according to the USGS.

How earthquakes are measured

Why was this one so deadly?

A number of factors have contributed to making this earthquake so deadly. One of them is the time of day it occurred. With the quake hitting early in the morning, many people were in their beds when it happened, and are now trapped under the rubble of their homes.

Additionally, with a cold and wet weather system moving through the region, poor conditions have made the rescue and recovery efforts on both sides of the border significantly more challenging.

Temperatures are already bitterly low, but by Wednesday are expected to plummet several degrees below zero.

An area of low pressure currently hangs over Turkey and Syria. As that moves off, this will bring “significantly colder air” down from central Turkey, according to CNN’s senior meteorologist Britley Ritz.

It is forecast to be -4 degrees Celsius (24.8 degrees Fahrenheit) in Gaziantep and -2 degrees in Aleppo on Wednesday morning. On Thursday, the forecast falls further to -6 degrees and -4 degrees respectively.

The conditions have already made it challenging for aid teams to reach the affected area, Turkish Health Minister Fahrettin Koca said, adding that helicopters were unable to take off on Monday due to the poor weather.

Despite the conditions, officials have asked residents to leave buildings for their own safety amid concerns of additional aftershocks.

With so much damage in both countries, many are starting to ask questions about the role that local building infrastructure might have played in the tragedy.

USGS structural engineer Kishor Jaiswal told CNN on Tuesday that Turkey has experienced significant earthquakes in the past, including a quake in 1999 which hit southwest Turkey and killed more than 14,000 people.

Jaiswal said many parts of Turkey have been designated as very high seismic hazard zones and, as such, building regulations in the region mean construction projects should withstand these types of events and in most cases avoid catastrophic collapses – if done properly.

But not all buildings have been built according to the modern Turkish seismic standard, Jaiswal said. Deficiencies in the design and construction, especially in older buildings, mean that many buildings could not withstand the severity of the shocks.

“If you are not designing these structures for the seismic intensity that they may face in their design life, these structures may not perform well,” said Jaiswal.

Jaiswal also warned that many of the structures left standing could be “weakened significantly because of those two strong earthquakes that we already witnessed. There is still a small chance of seeing an aftershock strong enough to bring those deteriorated structures down. So during this aftershock activity, people should take a lot of care in accessing those weakened structures for these rescue efforts.”